Research & Innovation

Jan 9, 2026

3D Printing 101: How Layer by Layer Manufacturing Is Quietly Reshaping the World

Rafiq Omair

On a typical afternoon in a university makerspace, a small crowd gathers around a humming box in the corner. Inside, a thin strand of plastic feeds into a heated nozzle. The print head traces a slow, deliberate path over a flat plate. Twenty minutes later there is something new in the world: a custom phone stand that did not exist this morning, designed and produced by a student who has never set foot in a traditional factory.

This is the everyday face of additive manufacturing. It began as a clever way to prototype parts. It has grown into a serious industrial technology that prints rocket engines, dental crowns, running shoes, and even sections of houses.

Image from: Bambu Lab A1 Combo 3D Printer High Speed, Multi-color

From Carving To Growing Objects

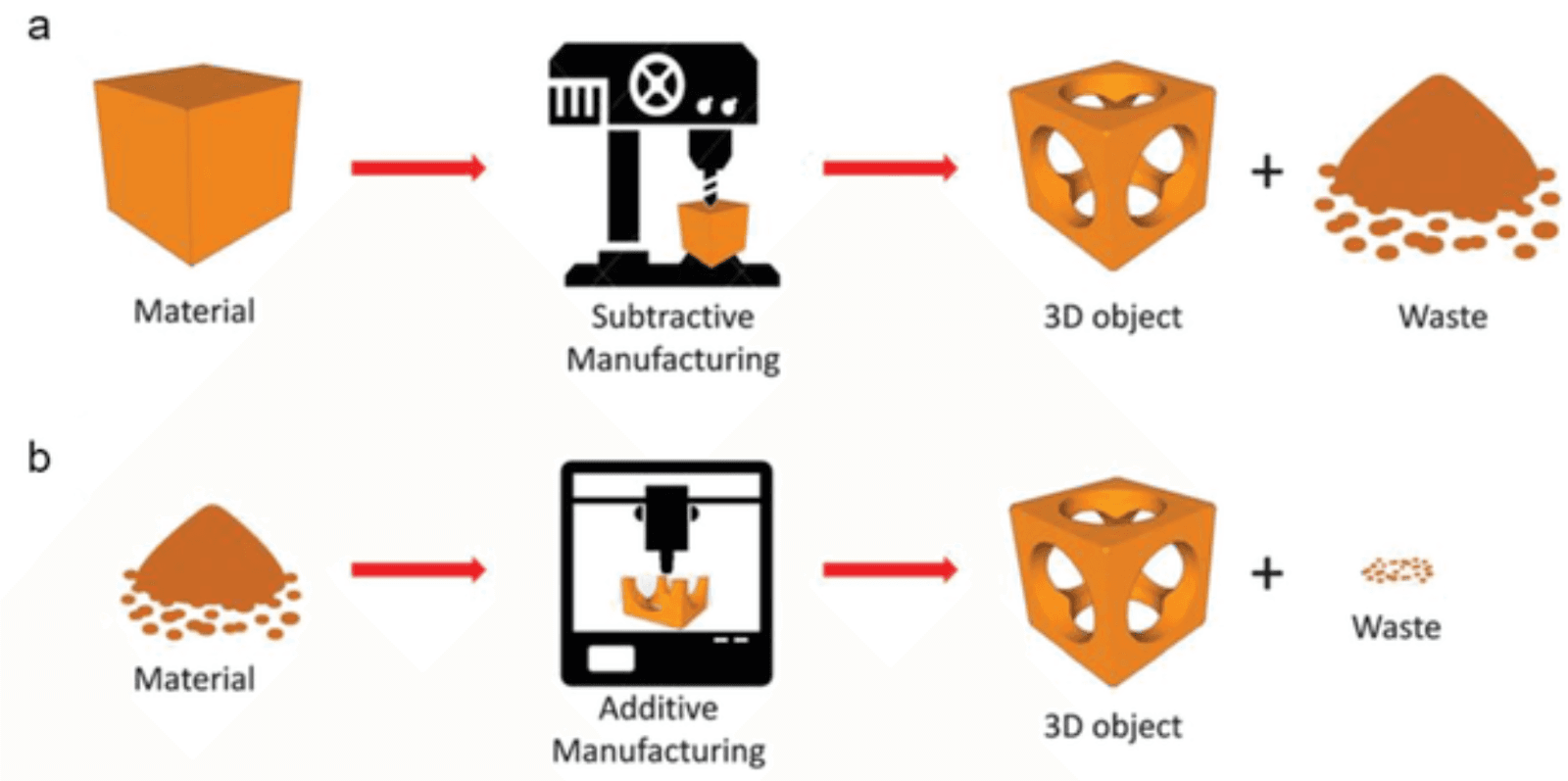

Image from Chen et al., 2020 (Additive Manufacturing of Piezoelectric Materials)

For most of human history, to make something solid you either carved it, cast it, or hammered it into shape.

Subtractive manufacturing starts with a block of material and removes what you do not want. Think of a machinist milling a metal part, or a sculptor carving stone.

Formative manufacturing uses molds or dies to force a material into shape. Think of casting metal, or injection molding plastic components by the million.

Additive manufacturing (AM) takes a different route. The machine reads a digital 3D model, then builds the object layer by layer, placing material only where it is needed. In practice that can mean molten plastic, cured resin, fused metal powder, or even pastes made from concrete or food.

It sounds like a small change. In reality it affects almost everything. When you are no longer limited by cutting tools or mold geometry, it becomes easier to:

Create complex internal structures, such as cooling channels and lattices.

Customize every part for a specific person or application.

Produce parts on demand, closer to where they will be used.

Reduce material waste, especially for expensive metals.

That is the logic that connects a dorm-room phone stand to a 3D printed rocket engine.

Inside A Typical Campus 3D Printer

Image from Original Prusa i3 MK3 and i3 MK3s

Most student makerspaces and hobby setups rely on a technology called Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM), also known as Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF). If you have ever watched a desktop 3D printer in action, you have probably seen FDM.

The workflow looks like this:

Design or download a model

The process starts on a computer. Someone designs a part in CAD, or downloads a ready-made model file.Slice it into layers

A program called a slicer takes that 3D model and divides it into hundreds or thousands of thin layers. It also generates the printer instructions, telling the machine where to move, how fast to travel, and how much plastic to extrude.Melt the filament

A thin plastic filament feeds from a spool into the printer’s hot end. It melts and flows through a small nozzle.Draw the part in 2D, then in 3D

The nozzle draws the first layer on the build plate, like a two dimensional outline filled with lines. Then the printer moves up by a fraction of a millimetre and draws the next layer on top. Slowly, the part rises out of the bed.Cool, remove, refine

Once printing is complete, the part is removed. Temporary supports may be snapped off. If appearance or precision matters, someone might sand, drill, or paint the surface.

There is a lot of engineering hiding in each of those steps. For now, it is enough to notice that the machine is stacking thin layers of material in exactly the right places. That is additive manufacturing in its simplest form.

Not All Plastics Are Created Equal

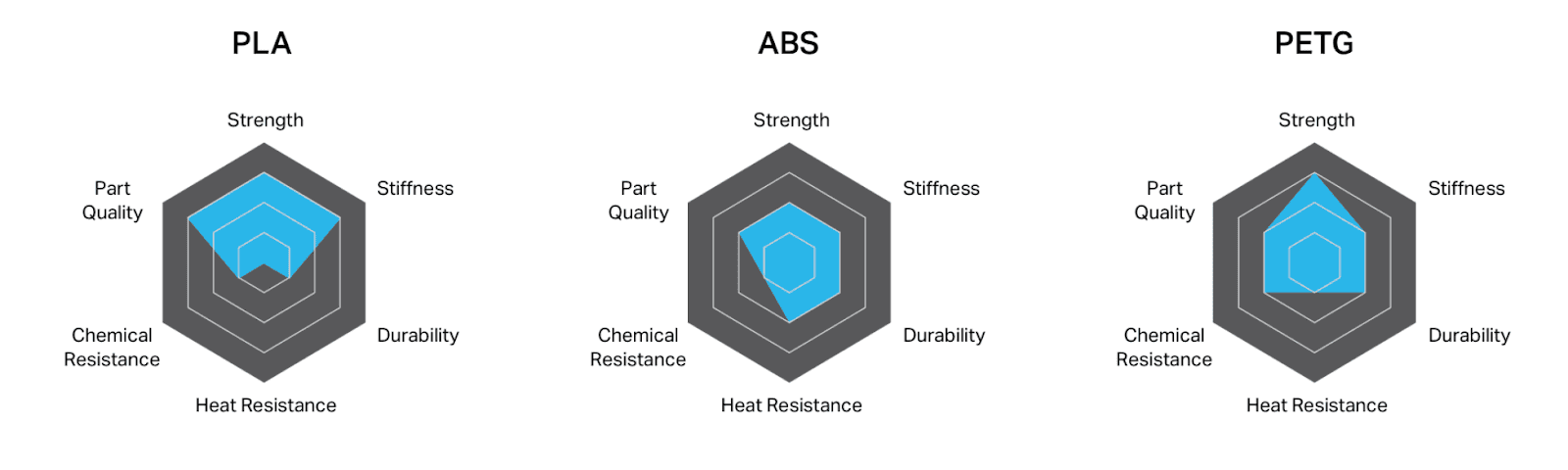

Image from 3D Printing Materials https://markforged.com/resources/learn/3d-printing-basics/how-do-3d-printers-work/3d-printing-materials

To a beginner, spools of filament all look roughly the same. In practice, the choice of material is one of the most important decisions you can make.

PLA: The Friendly Default

PLA (Polylactic Acid) is the first stop for many new users. It melts at relatively low temperatures, sticks well to the build plate, and is less prone to warping. It is also often derived from renewable sources such as corn or sugarcane.

The tradeoff: PLA is brittle and softens in heat. A phone mount left on a hot car dashboard might slowly droop.

PLA is ideal for visual models, prototypes, figurines, and student projects where ease of use matters more than mechanical performance.

ABS: Strong, If You Treat It Right

ABS (Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene) is the plastic behind many commercial products, from toys to automotive interior parts. It is strong, impact resistant, and handles heat better than PLA.

The catch is that ABS is sensitive to temperature gradients. As it cools, it tends to warp or crack between layers. In practice that means it prefers an enclosed printer with a heated chamber and proper ventilation. In the right environment, it is excellent for tougher housings and functional parts.

PETG: The Everyday Workhorse

PETG (Polyethylene Terephthalate Glycol) feels more like a practical engineering plastic. It is tougher than PLA, less brittle, and more tolerant of higher temperatures. Parts printed in PETG can flex slightly before breaking, which is useful for clips, brackets, and functional components.

It can string if settings are not tuned, but once dialed in it becomes a favourite for lab fixtures and light duty mechanical parts.

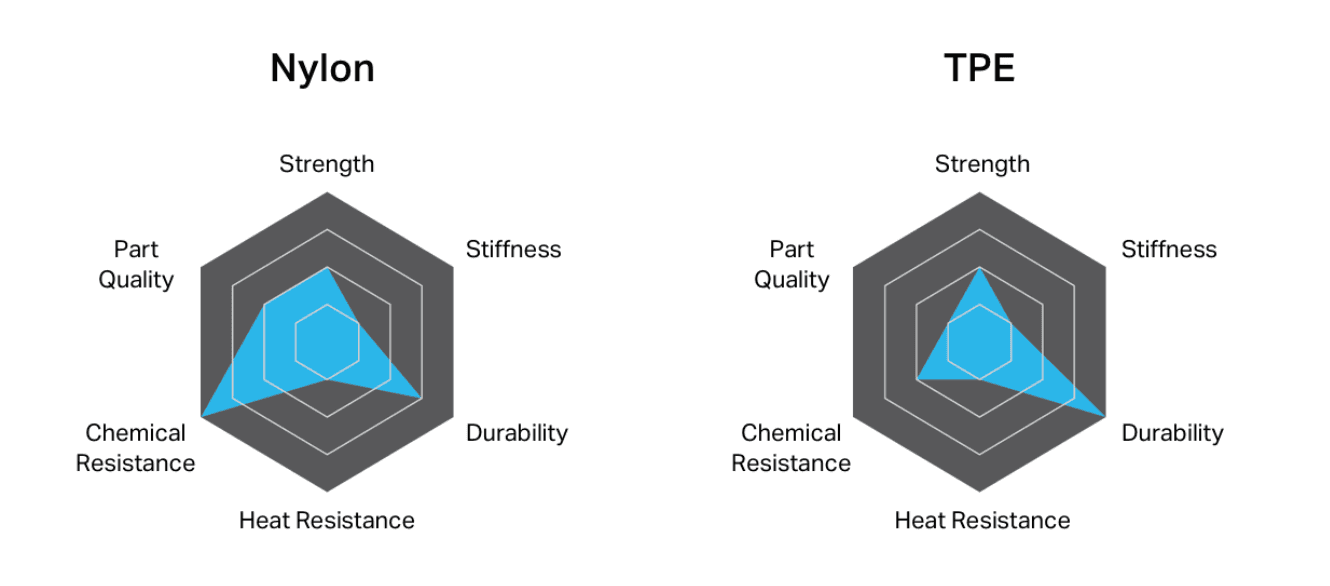

Nylon: Engineering Grade

Nylon sits closer to traditional engineering plastics. It combines strength, toughness, and good wear resistance, which makes it well suited for gears, bushings, and structural parts.

Nylon has quirks too. It absorbs moisture from the air, which can ruin print quality if it is not thoroughly dried before use. It also prints best at higher temperatures. In return, you get parts that start to feel like serious mechanical components rather than prototypes.

By experimenting with the same design in PLA, PETG, TPU, and nylon, students quickly learn a fundamental lesson in engineering: material choice is design.

TPU: The Bendy One

TPU (Thermoplastic Polyurethane) changes the game again. Instead of rigid pieces, you get prints that bend, stretch, and bounce back.

Flexible filaments are used for phone cases, vibration mounts, grippy surfaces, and wearable components. They demand patience, since soft filament is harder to push accurately through an extruder, but the range of applications is completely different.

Beyond Plastic: Resin And Metal

So far this sounds like a story about plastic spaghetti. To see the bigger picture you need to look at two other families of technology: resin printing and metal additive manufacturing.

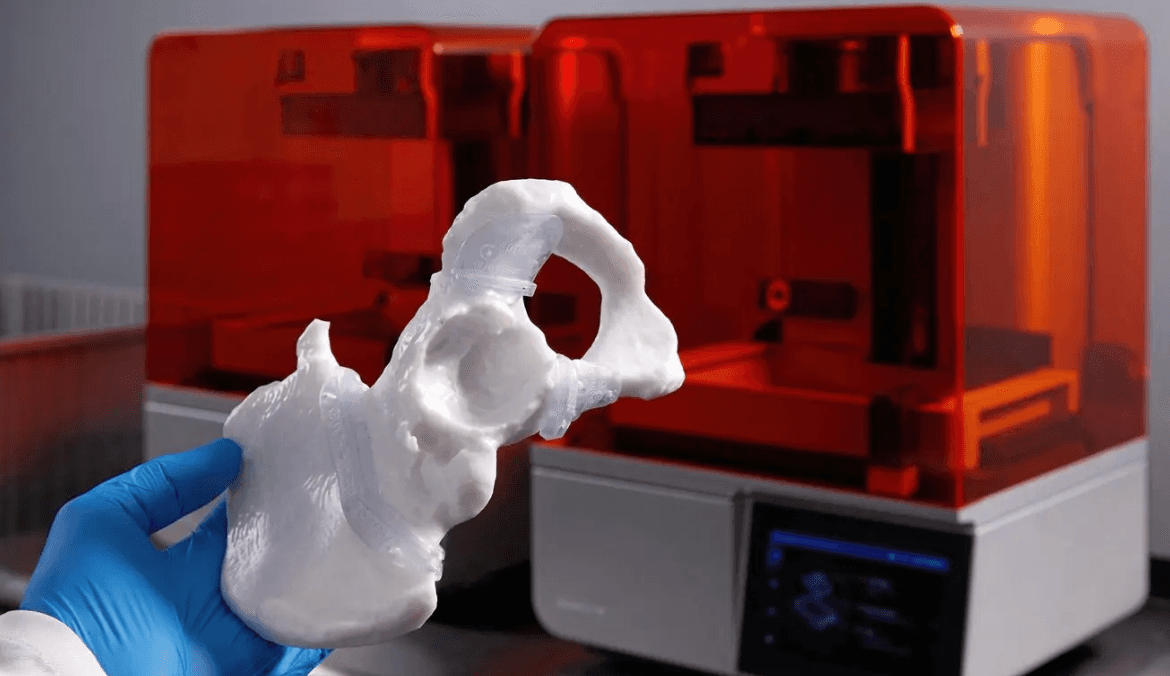

Resin Printing: Formlabs And The Dentistry Revolution

Resin printers replace filament with a shallow pool of liquid photopolymer. A light source cures the resin layer by layer, creating extremely detailed parts with smooth surfaces. This method is often called SLA or DLP, depending on the light engine.

Companies such as Formlabs have turned resin printing into a compact, relatively affordable tool for dentists, medical device makers, and engineers. Dental clinics now routinely scan a patient’s teeth, design a custom aligner or surgical guide, and print it in house in a matter of hours. The patient sees a plastic aligner. Behind the scenes they are wearing the result of a digital design and additive manufacturing workflow.

Metal Printing: From EOS And HP To Rocket Engines

Metal additive manufacturing replaces plastic filament with powder made from alloys such as titanium, aluminium, or nickel based superalloys.

In laser powder bed fusion, a machine spreads a thin layer of powder and uses a high power laser to selectively melt the areas that will become solid metal. The process repeats, layer upon layer, until a fully dense part is buried in a cake of loose powder.

Companies like EOS specialize in these systems for aerospace, energy, and medical implants. HP has entered the field with its own approaches to both polymer and metal printing for industrial users.

The appeal is simple and powerful. Designers can produce parts with internal channels for cooling, lightweight lattice structures, and shapes that would be almost impossible to machine. Rocket engines, heat exchangers, and orthopedic implants are all early beneficiaries.

A Tour Of Additive Manufacturing Innovation

With the basics in place, it is worth looking at how different sectors are using these tools in ways that would have sounded like science fiction a generation ago.

Rockets: Relativity Space

Image from Relativity

In the launch industry, Relativity Space has built its identity around metal 3D printing. The company aims to produce a large fraction of each rocket, including key engine components, with additive processes.

Printing complex engine parts reduces the number of individual pieces and welds, which can simplify manufacturing and create internal cooling passages that follow curved, organic paths. It also allows rapid iteration. A design that once required new tooling can now be updated in software and printed directly.

The result is not just a cooler looking engine. It is a potential shift in how quickly aerospace companies can move from concept to hardware.

Housing: ICON And Printed Neighborhoods

Image from ICON

On construction sites in the United States and beyond, ICON is experimenting with large scale printers that extrude a cement based mix and trace the outline of house walls.

From a distance it looks like a giant FDM printer turned sideways. A gantry or robotic arm moves a nozzle around a building footprint, stacking bead on bead of structural material. Human crews follow behind to install rebar, windows, roofs, plumbing, and wiring.

ICON has already completed small communities of printed homes. The promise is speed, reduced manual labor, and new architectural freedom, particularly for curved or non standard layouts. The questions now revolve around building codes, long term durability, and economics.

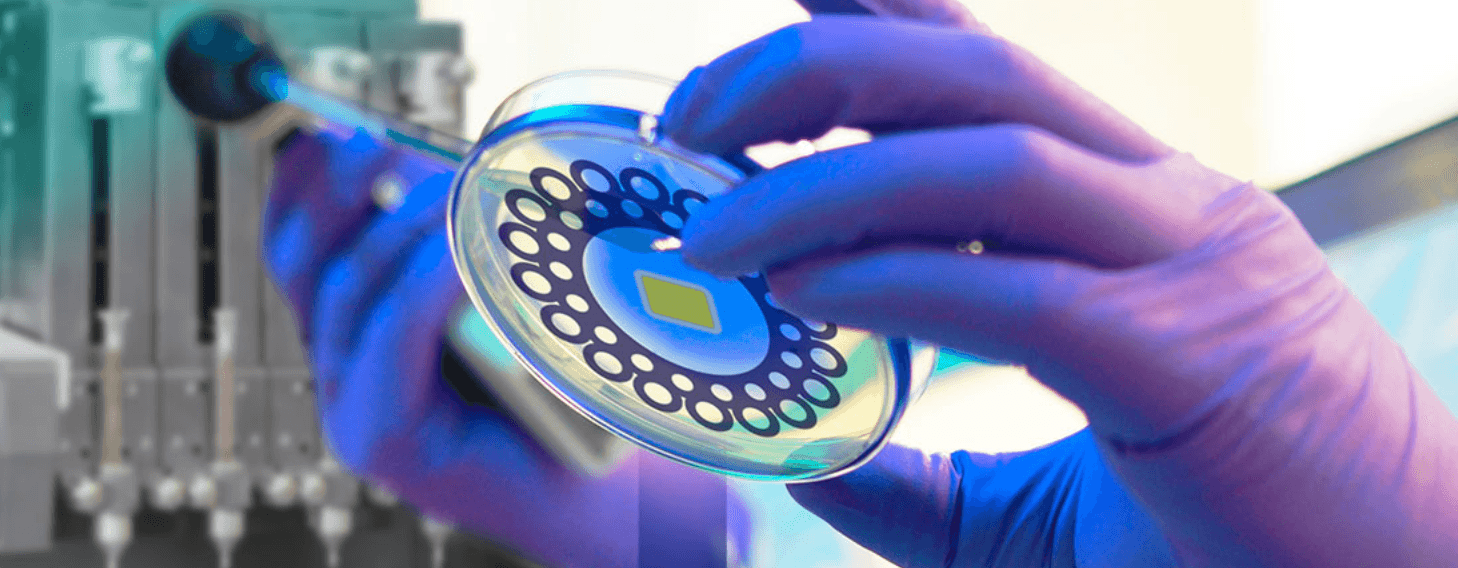

Bioprinting: CELLINK And Organovo

Image from Organovo

In the life sciences, companies such as CELLINK and Organovo are exploring how to print living cells.

Bioprinters dispense bioinks that contain cells and supportive materials in carefully designed patterns. Researchers use them to create tissue models for drug testing, disease research, and early steps toward regenerative medicine.

Printing a fully functional human organ is not something we can do today. What is already real is the ability to create lab grown tissues that more closely mimic human biology than a flat layer of cells in a dish. Additive manufacturing principles are central to that progress.

Footwear: Adidas And Carbon

Image from 4DFWD 4 Running Shoes, Adidas

Look under the heel of certain high end Adidas running shoes and you will find a strange, lattice like midsole. That structure comes from a partnership with the 3D printing company Carbon.

Carbon’s process uses light and oxygen to rapidly cure liquid resin into intricate geometries. Instead of a uniform block of foam, the midsole becomes a precisely tuned network of struts and voids. Designers can change the stiffness and energy return in different regions under the foot without changing the external shape of the shoe.

The idea is simple: combine digital design, simulation, and additive manufacturing to deliver performance and personalization that traditional foam cannot easily match.

Food Printing: Natural Machines And Redefine Meat

Image from Foodini, Natural Machines

Additive manufacturing has even crept into the kitchen.

Natural Machines produces the Foodini, a countertop device that extrudes pureed ingredients through nozzles to create intricate shapes and textures. In professional kitchens the goal is not to replace chefs, but to extend what is possible in presentation and portion control.

Companies like Redefine Meat apply similar ideas to plant based foods. By carefully placing different materials, they try to mimic the layered texture of animal muscle and fat. The result is closer to a structured steak than a simple burger patty.

It is still early days, but the underlying logic is familiar: treat food as a material that can be shaped additively and digitally.

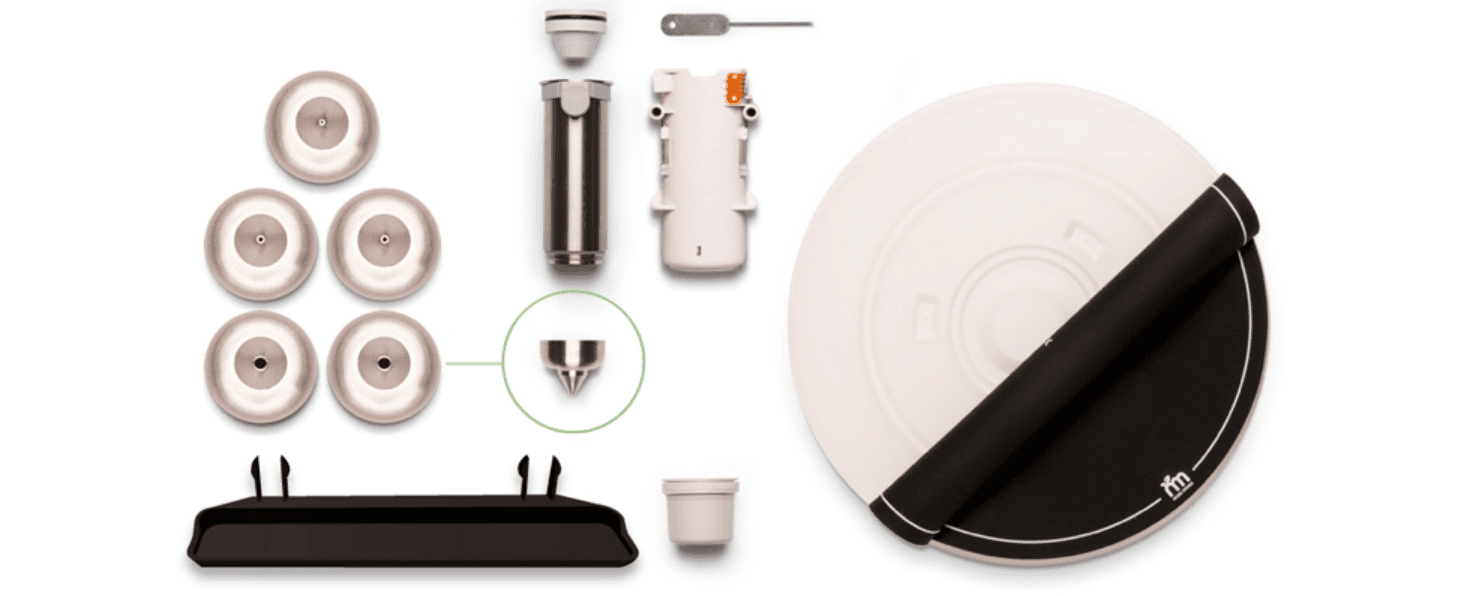

Dental And Medical Devices: Formlabs And Friends

Image from Formlabs

Returning to resin printing, the dental sector is one of the clearest real world success stories. With printers from companies such as Formlabs, labs and clinics routinely produce clear aligner models, surgical guides, crowns, and custom trays.

Scans replace impressions. Digital files replace physical molds. Additive manufacturing turns what used to be a multi day, multi step process into something that can fit inside a single clinic and a single working day.

Why It Matters For Students And Curious Readers

It is tempting to see 3D printing as a niche hobby or a futuristic gimmick. The examples above suggest something different.

Additive manufacturing is:

A design tool, because it frees you from many traditional constraints.

A manufacturing method, already used at scale in aerospace, dentistry, and footwear.

A learning platform, perfectly suited to students who want to see their ideas become physical objects.

If you are new to all of this, a simple next step is to visit a campus makerspace or local library that has a 3D printer. Watch a print from start to finish. Then design something modest, like a cable clip or a custom bracket, and see what happens when you change the material, infill, or orientation.

Behind that small object is the same set of ideas driving Relativity’s rockets, ICON’s houses, Carbon’s midsoles, and the bioprinted tissues growing in laboratory incubators. All of it begins the same way: with a digital model, a print command, and a thin first layer of material placed exactly where it needs to be.