Research & Innovation

Jan 18, 2026

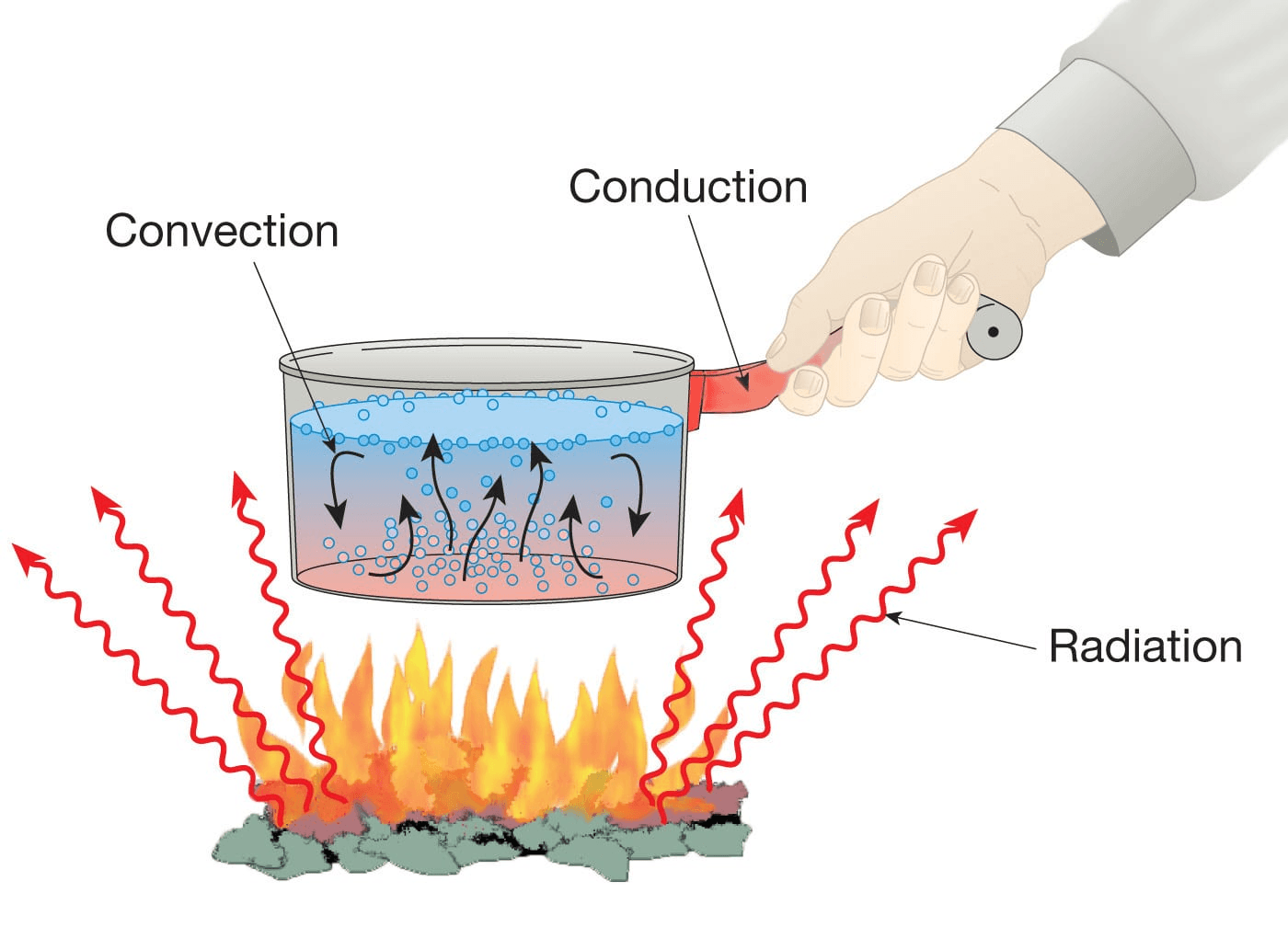

How Heat Really Moves: A Guided Tour of Conduction, Convection, and Radiation

Rafiq Omair

On a winter morning, you pour coffee into a cold mug and watch thin curls of steam rise. The mug warms your hands, the coffee cools, and the room air quietly carries the heat away. Nothing about that scene looks unusual, yet three core ideas in engineering are at work.

Heat is on the move.

This article unpacks the three main methods of heat transfer: conduction, convection, and radiation. The aim is to stay readable for non-specialists and still give engineering students a solid mental model for later courses and design work.

What Do We Actually Mean By "Heat"?

Image from SimScale

In physics, heat is not a substance. It is energy in transit, moving from something hotter to something colder.

A hot object has atoms and molecules that jiggle and vibrate more. A cold object has particles that move less. When they interact, energy flows from the faster-moving particles to the slower ones. That flow is heat transfer. It always goes from higher temperature to lower temperature, unless you use a machine such as a refrigerator or heat pump that spends work to push heat the other way.

How that energy moves depends on the situation. That is where conduction, convection, and radiation come in.

1. Conduction: Heat by Direct Contact

Place a metal spoon in hot soup and wait a minute. When you grab the handle, it feels warm or even painful. The soup did not climb the spoon. Instead, heat travelled through the material. That is conduction: heat transfer through a solid, or a stationary fluid, by direct molecular collisions.

Inside a solid, atoms sit in a lattice and vibrate. In a metal, free electrons also carry energy. When one region is hotter, its atoms vibrate more and bump into their neighbours, passing energy along step by step.

Engineers describe conduction with thermal conductivity, which measures how easily heat flows through a material. Copper and aluminum have high thermal conductivity. Wood, foam, and fibreglass have low thermal conductivity and act as insulators.

That is why a metal pot heats quickly on a stove while the plastic handle stays safe to hold, and why house walls include insulation to slow heat flow from indoors to outdoors.

2. Convection: Heat Riding on Moving Fluids

Conduction explains why the spoon gets hot. It does not explain why your coffee produces rising steam plumes or why a breeze makes you feel colder.

That is convection: heat transfer by the movement of a fluid, usually a liquid or a gas. Here, the fluid itself moves and carries heat with it.

In natural convection, motion arises on its own because of density differences. Heating a region of fluid makes it expand slightly and become less dense. The warmer, lighter fluid rises while cooler, denser fluid sinks to replace it. The resulting circulation transports heat. Warm air rising from a radiator and steam rising from a cup of tea are both examples.

In forced convection, an external device pushes the fluid: a fan blowing over a hot laptop, a pump circulating coolant in a car engine, or an air conditioning system moving air through ducts. By forcing the fluid to move faster, you increase the rate at which it carries heat away from a surface.

This is why a fan can make you feel cooler, even if it does not change the air temperature, it enhances convective heat loss from your skin.

3. Radiation: Heat as Invisible Light

Conduction needs contact. Convection needs a fluid. Yet the Sun heats Earth across the vacuum of space. No air molecules are available to collide, and nothing is circulating between the Sun and you.

That is thermal radiation: heat transfer by electromagnetic waves, mainly in the infrared region.

Every object above absolute zero emits radiation. Hotter objects emit more energy and at shorter wavelengths. A warm wall emits mainly infrared, which you cannot see. A red-hot stove coil emits visible light as well as infrared. The Sun emits a broad spectrum that includes ultraviolet, visible, and infrared.

Radiation has two key features that set it apart. It does not need a medium; it can cross a vacuum. And surface properties matter a lot. Matte black surfaces tend to be strong emitters and absorbers. Shiny metal surfaces tend to emit and absorb less.

When you feel the warmth of a campfire from several metres away, or the Sun on your face on a clear day, radiation is doing most of the work, not the air temperature itself.

How the Three Work Together

In real situations, you almost never have pure conduction, convection, or radiation in isolation. All three are usually involved.

Return to the coffee on the table. The hot coffee warms the mug by conduction through the contact surface and through the ceramic wall. Warm air just above the coffee becomes lighter and rises, while cooler room air flows in to replace it, so convection carries heat away. The hot coffee and mug also emit infrared radiation to the walls, table, and surrounding air.

Change any one pathway, and you change how quickly the coffee cools. A thicker, better-insulated mug reduces conduction outward. A lid suppresses convection from the surface. A reflective sleeve reduces radiative losses.

The same pattern applies to a building, a radiator, a phone, or a satellite; multiple heat transfer mechanisms act at once. Good design is often about deciding which ones to encourage and which to block.

Everyday Design Through a Heat Transfer Lens

A house in winter is a battle between the warm interior and the cold outdoors. Conduction is slowed by insulation in walls and roof, which traps pockets of still air with low thermal conductivity. Convection within the insulation is limited because the pockets are small and cannot circulate effectively. Radiation through windows is reduced by coatings that reflect infrared back into the room.

A thermos flask uses the same ideas in more extreme form: a vacuum layer to eliminate conduction and convection, and a reflective surface to cut down radiation.

6Why It Matters For Students And Curious Readers

For a curious reader, understanding heat transfer explains everyday experiences: why coffee cools, why a breeze feels cold, and why radiators sit under windows. For an engineering student, it is also the beginning of a larger toolkit.

For a curious reader, understanding heat transfer explains everyday experiences: why coffee cools, why a breeze feels cold, and why radiators sit under windows. For an engineering student, it is the beginning of a larger toolkit.

Thermal management limits the performance of batteries, power electronics, and high-performance computing.

Comfort and energy efficiency in buildings depend on controlling conduction through walls, convection around occupants, and radiation through windows and roofs.

Safety in everything from nuclear reactors to lithium-ion battery packs involves guiding heat away from critical regions and keeping temperatures within limits.

Courses will introduce the equations: Fourier’s law for conduction, Newton’s law of cooling for convection, and the Stefan Boltzmann law for radiation. Behind those formulas are the intuitive stories you already know.

Touch a hot pan and you feel conduction, stand in front of an open oven and you feel convection from the hot air and radiation from the glowing elements, step into the shade on a hot day and the air may be the same temperature but you feel instant relief because you have just cut off a major radiative heat source.

The methods of heat transfer are not just textbook headings. They are the quiet rules that govern how every warm, cold, or comfortable object around you interacts with its surroundings.